The Final United Nations Conference on the Arms Trade Treaty failed to reach consensus because the draft text offended state sovereignty.

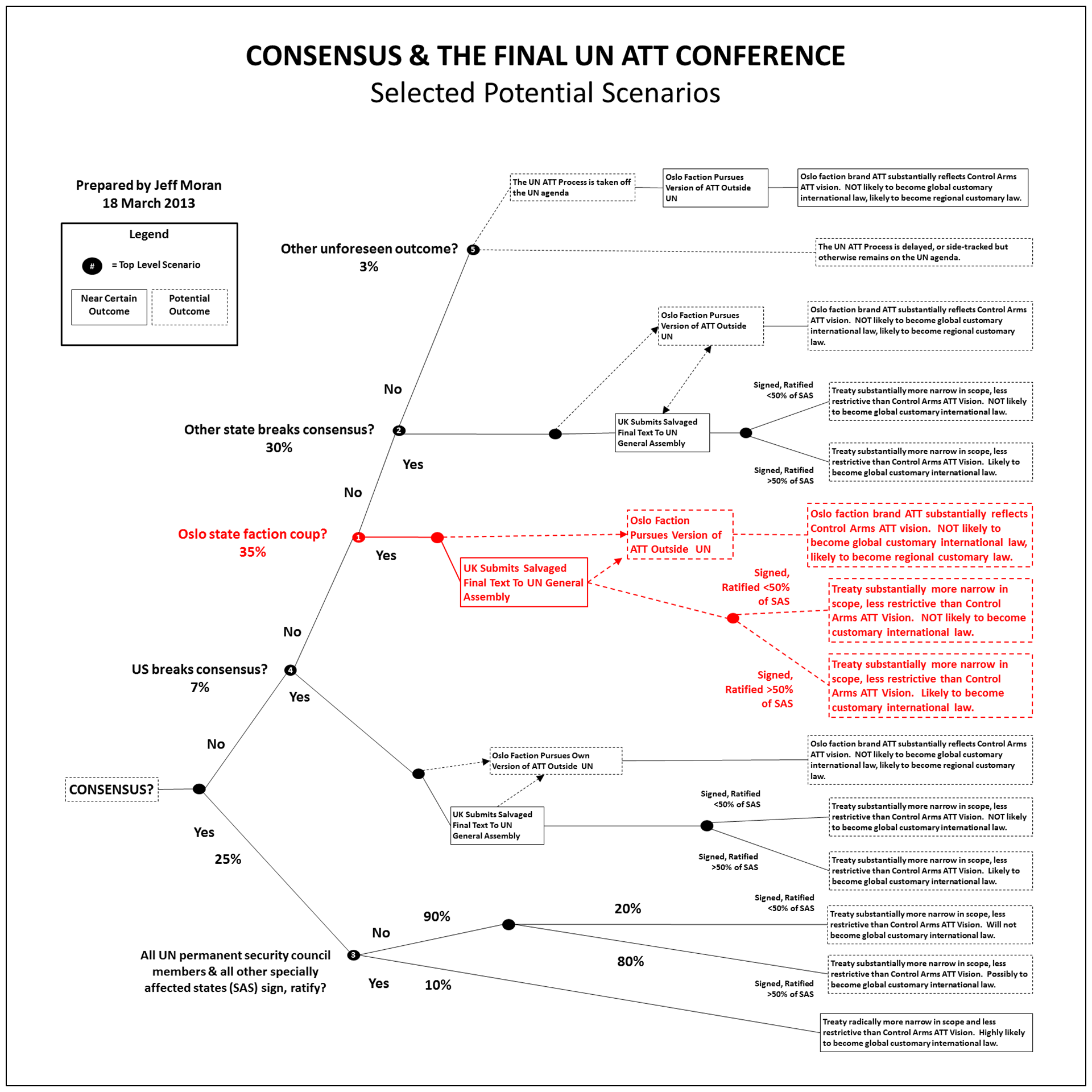

The Final United Nations (UN) Conference on the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) failed to reach an agreement by consensus yesterday. And this hardly comes as any surprise. Going into the Conference, this author estimated the probability of not reaching consensus to be 75%. The reasons for this were detailed in a pre-conference Executive Brief published on Amazon.com. Here is a model to help illustrate how things could and have played out (click to enlarge):

The key thing one should take away from this model is that consensus was only 25% likely, and it now looks like the situation is following scenario #2. Scenario #1 (in red) did not happen because the Oslo faction succeeded in championing more of its interests relative to authoritarian states with concerns for sovereignty. In fact, the Executive Brief, titled Unlikely Consensus: Commentary and Outlook for the United Nations Conference on the Arms Trade Treaty, correctly estimated the that if the Oslo faction didn’t break consensus, the consensus killer(s) would be Iran, Syria, and/or North Korea, and that the reason would be rooted in concerns raised over sovereignty.

The final ATT conference failed in the end for the exact same reasons the ATT conference failed last summer. It was the result of overdone advocacy by the Oslo faction. The Oslo faction is a subset of states led more or less by Norway, Austria, and Mexico. The faction importantly includes a constellation of supporting humanitarian and disarmament non-governmental organizations (NGOs) whose members have even been direct participants in the ATT negotiations on state delegations. (Read more about why the ATT conference failed last summer here).

Some argue that the US is really to blame for demanding the ATT be negotiated by consensus rules (versus a simpler 2/3 majority rule). But this is wrong, and unfair. The US had no real choice but to demand this rule because it is the only country (other than maybe Yemen) that has a Constitution and legal history protecting an individual’s natural right to armed self-defense with arms commonly used for such purposes.

If the ATT was negotiated by 2/3 majority rule, the treaty would have been even more aspirational and humanitarian than it already is (click here for treaty text). If there was no consensus rule, the ATT probably would have been identical to the 2004 Nairobi Protocol and the 2010 Kinshasa Convention. These two treaties (signed by 11 Central African states) entail such things as a ban on private ownership of all semi-automatic rifles, an international by-name ownership registry of arms and ammunition, and the strict regulation (e.g. marking and tracing, ownership registries) of any parts, components, and equipment used for the manufacture, assembly, or repair of any arms and ammunition. (Read more about these treaties here)

If one assumes that states (i.e. their leaders) act in accordance with perceived interests, the failure of the ATT conference to reach consensus was entirely reasonable. Blaming Iran, Syria, and North Korea is therefore a waste of time if not completely self-serving. These states may have killed consensus, but this was their right, and they were not alone in their concern. India and Pakistan have been outspoken too. China and Russia may not have broken consensus, but they may not sign the treaty when it comes up for a vote in the UN General Assembly (UNGA). For these states, the sovereignty concern is clear whether the text was not strong enough on the right for states to obtain weapons in self-defense, on prohibiting arms transfers to rebel groups, or on equitably balancing the interests of importing states with exporting ones for example.

Going forward, the Arms Trade Treaty will be put before the UNGA soon, perhaps as early as Tuesday next week. Assuming the Oslo faction doesn’t declare complete shenanigans and start up a new treaty process outside the the UN, well over 100 states will probably sign the treaty in the UNGA. The UK will sign and ratify it (it is their special project after all). China and Russia probably won’t sign. And the US probably will sign, but won’t ratify for decades if ever. France might not sign or ratify, which wouldn’t be surprising given its apparent predilection for questionable arms transfers of late. This all means the ATT will likely follow in the footsteps of the 1997 treaty to ban landmines or the 2008 treaty to ban cluster munitions. Like the ATT, these other treaties came into being as a direct result of humanitarian advocacy. But more importantly, these treaties are largely symbolic and not globally binding as either treaties or as customary international law. This is because they lack key signatures and ratifications by specially affected states (i.e. the critical mass of states that make or use landmines or cluster munitions).

In conclusion, it should be no surprise that the Final UN ATT Conference failed to reach consensus. This failure was a reasonable and predictable outcome based in national interests. It did not fail because diplomacy failed, but because humanitarian advocacy was too effective on many influential diplomats. Rightly understood, the draft treaty failed to achieve consensus as a result of an over-representation of Oslo faction state interests, and the under-representation of more authoritarian state interests and the interests of importing states. Ultimately, the Olso faction sabotaged themselves by pushing diplomats too hard for far too much and provoking dispositive anxieties over sovereignty.

About The Author

Jeff Moran lives in Geneva, Switzerland and is a consultant specializing in the international defense, security, and shooting sports industries at TSM Worldwide LLC. Previously Mr. Moran was a strategic marketing leader for a multi-billion dollar business unit of a public defense & aerospace company and an American military diplomat. He is currently studying weapons law within the Executive LL.M. Program of the Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights. Mr. Moran has an Executive Master in International Negotiations and Policymaking from the Graduate Institute of Geneva, an MBA from Emory University’s Goizueta Business School, and a BSFS from Georgetown University’s Walsh School of Foreign Service.

First Published: 29 March 2013

Last Updated: 29 March 2013

Distribution Notice

Online republication and redistribution are authorized when this entire publication (including byline, hyper-links, About the Author and End Note sections) and linkable URL https://tsmworldwide.com/humanitarian-hijacking/ are included. See other published items at https://tsmworldwide.com/category/published/