The invalid assumptions behind the United Nations’ small arms control initiatives

[Note: this article is currently being rewritten in light of recent events and the compilation of many more invalid assumptions]

By Jeff MORAN | Geneva

Next month diplomats from the world over will converge at the United Nations in New York to formally negotiate a legally binding Arms Trade Treaty (ATT). This is the culmination of over a decade of humanitarian advocacy and pre-negotiations inside and outside the United Nations. It’s part of a larger global effort kick-started in 2001 with the adoption of a non-legally binding program of action at the United Nations Conference on the Illicit Trade in Small Arms and Light Weapons in All Its Aspects in 2001. This program was formally called the “Programme of Action to Prevent, Combat and Eradicate the Illicit Trade in Small Arms and Light Weapons in All Its Aspects” (PoA).[1] This led to the creation of many initiatives, the most visible and contentious of which has been the ATT.

The ATT process formally got underway with two subsequent UN resolutions lead by the United Kingdom and is still Chaired by Argentine Ambassador Roberto Moritán. In 2006, the UN General Assembly adopted resolution 61/89 entitled “Towards an arms trade treaty: establishing common international standards for the import, export and transfer of conventional arms.” [2] This resolution enabled the UK and like-minded countries to assemble experts to assess the feasibility of formally launching an ATT negotiation process. Then, in 2009, the UN General Assembly adopted resolution 64/48, entitled “The Arms Trade Treaty,” which established a schedule for pre-negotiation meetings (known as Preparatory Committees, or PrepComs) resulting in a final Diplomatic Conference in July 2012. [3]

The goal of the ATT is to “to elaborate a legally binding instrument on the highest possible common international standards for the transfer of conventional arms.”[4] The scope is likely to include everything from helicopters to hand grenades, from tanks to target pistols and ammunition. It is hoped by humanitarians that a legally binding UN ATT championed by like-minded states could be shaped to complement the merely politically-binding 2001 UN PoA.

While all this treaty advocacy was going on, many of the same actors adopted an additional and more discreet approach to binding international law for small arms and ammunition. Rather than just pursue their ambitious goals through a treaty out in the open, they also quietly started developing small arms control standards. An example of this is the UN CASA (Coordinating Action on Small Arms) project, which is overseen by the UN’s Office of Disarmament Affairs. [5] UN CASA is euphemistically described as the “small arms coordination mechanism within the UN” to “frame the small arms issue in all its aspects, making use of development, crime, terrorism, human rights, gender, youth, health and humanitarian insights.” [6] In practice this organization is like a lawmaking committee or agency, but not nearly as accountable.

In 2008, CASA launched what they themselves described as “an ambitious initiative to develop a set of International Small Arms Control Standards (ISACS).” [7] UN CASA’s ISACS project includes eighteen mostly small and developing countries (none of them permanent security council members), fifteen international, regional and sub-regional organizations, 33 humanitarian civil society groups, 23 other UN bodies, and just one Belgian firearms company, and one Italian national sporting arms and ammunition industry association. [8]

Ultimately, UN CASA’s ISACS initiative is about creating “soft law” that is hoped to eventually harden into something more formally and generally binding. Soft law could be hardened by translation into treaties or simply by widespread adherence and acceptance as international custom. States can be bound by customary international law regardless of whether the states have codified these laws domestically. Standards or soft law may be used to inform the interpretation of treaties as well. Along with general principles of law and treaties, customary law is considered to be among the primary sources of international law identified from Article 38(1) of the Statue of the International Court of Justice. Article 38(1) is recognized as the classic statement of the sources of international law. [9]

Truth be told, the UN’s PoA, the ATT, and CASA ISACS are predicated on false assumptions regarding small arms and ammunition. The two most important of which I will discuss here. Both of these assumptions are generally false in view of statistical studies and published scholarship.

The first assumption is that proliferation of small arms is a universal threat to humanity, or, alternatively, that greater availability of small arms means more gun deaths in a given society. This is best quoted by the Geneva-based Small Arms Survey (SAS), a special interest research group funded by various United Nations organizations, and other countries advocating stricter small arms controls. [10] The SAS officially states that the driving assumption behind all their research is the unqualified universal idea that “proliferation of small arms and light weapons represents a grave threat to human security.” [11] In fact, Nicholas Florquin, a senior researcher at SAS, started his talk during a two day seminar on Small Arms and Human Security in November 2011 with a stronger statement that, “proliferation of small arms causes problems” for humanity. [12]

Clearly, the small arms situation in some places may indeed be out of hand, and that this can pose a societal hazard. But proliferation, i.e. the distribution of arms or expanding private ownership of arms, is not intrinsically a bad thing for everyone everywhere, especially in an ordered society. Proliferation, in fact, can be a force for good even in a disordered societal situation.

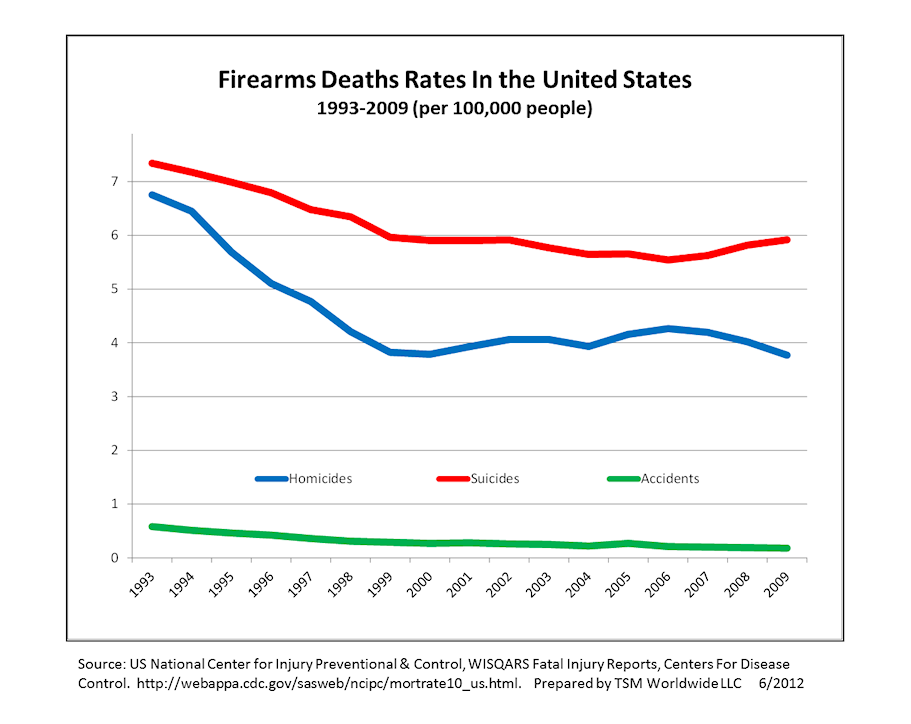

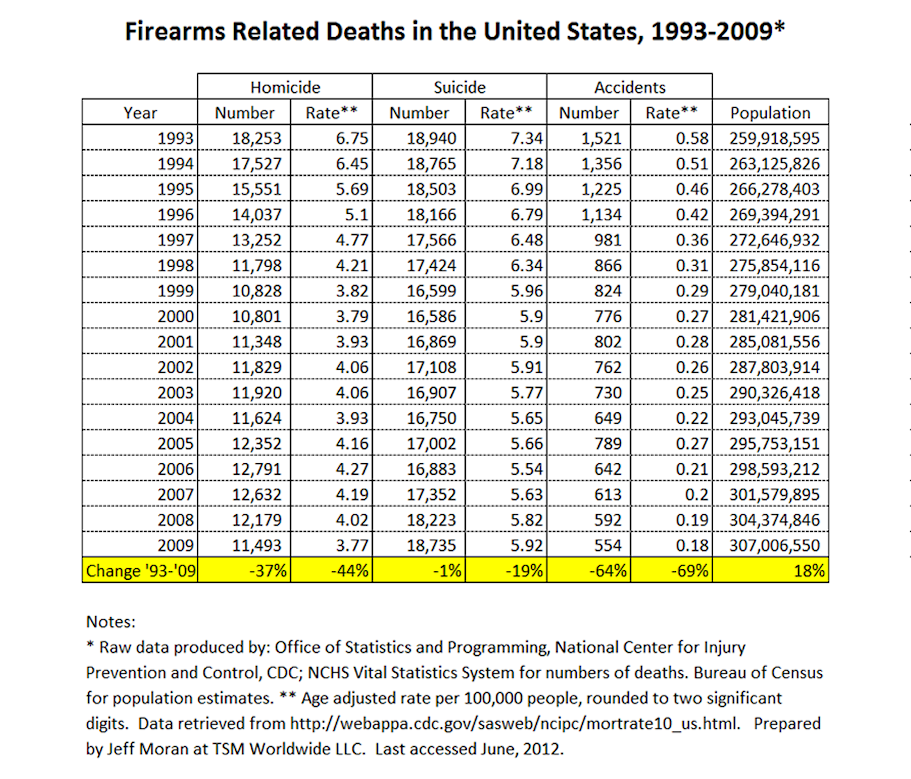

The American experience alone invalidates the global causative relationship between small arms proliferation and deaths from small arms. For example, trend data over the past nearly 20 years shows the US has been experiencing a phenomenal decline in gun-related deaths per 100,000 people. Specifically homicides, suicides, and accidents have decreased 44%, 19%, and 69% respectively. [13] This is part of a long term general trend in lower criminality. Over the same period the population grew nearly 20%, gun availability spiked (firearms sales boomed while statistically insignificant numbers of guns were removed from society by government or were otherwise destroyed), and, in 2011, indicators of national gun ownership rates increased to their highest level since 1993. [14,15] In other words, what we see in the US is the flipside of the assumption, that proliferation of small arms coincides with less gun violence. While this situation doesn’t necessarily mean more guns causes less gun violence, it does mean that the global “small arms proliferation means more gun deaths” assumption is simply not valid.

The French experience arming revolutionaries abroad invalidates the global moral aspect of this first assumption, that proliferation is intrinsically bad. In fact, France alone has shown there can be a democratic and human rights upside of small arms proliferation. Have humanitarian campaigners forgotten that France armed liberty-seeking American revolutionaries against colonial Britain?These experiences prove even questionable state-sponsored small arms proliferation to “insurgents” and “revolutionaries” can actually be a good thing for some societies and their local humanity.

The second assumption is that there is a plague of international illegal weapons trafficking threatening humanity everywhere. In fact, Rachel Stohl, the long-time private consultant and insider working directly for Ambassador Moritán managing the ATT processes, has even published that “Without a doubt, it is the illegal arms trade and its various actors, agents, causes and consequences that capture our attention and motivate our action.” [16]

New research suggests the problem of illicit international trade in arms is not nearly as bad as first hypothesized over 10 years ago. Humanitarian campaigners’ evidence about the vast size, global scope, and cataclysmic impact of international illicit trafficking simply does not exist. Granted, it’s hard to quantify such illegal activity. Nonetheless, the assertion that illicit international small arms trafficking is a major problem for the world has in fact been disproven over 10 years of progressively improved knowledge on the topic by academics and specialist researchers. [17]

To this day, however, the UN still claims on its Office of Disarmament Affairs website that international trafficking is a “worldwide scourge,” and that it “wreaks havoc everywhere.” [18] Campaigners, and their UN organizational sympathizers, have yet to embrace the truth and acknowledge that the world is NOT actually suffering from a scourge of illegal international arms trafficking everywhere. At its worst, some failed or fragile states, conflict or post-conflict regions may be suffering from illegal trafficking, but even this is of dubious importance ranked against other concerns like local diversion of small arms from government arsenals. Deaths and violence by small arms and light weapons are, on the whole, symptomatic of more local causes rooted within societies, and not cross-border transfers.

The inconvenient truth today for humanitarian campaigners for international small arms controls is that for most countries around the globe, even for most developing or fragile states, a combination of deficient domestic regulation of legal firearms possession with theft, and loss or corrupt sale from official inventories is a more serious problem than illicit trafficking across borders. [19] And this implies a change imperative for improving local governance with customized solutions in affected countries and regions, not developing a one-size-fits-all legally-binding global governance system for small arms and ammunition. The much touted scourge of illicit trade in small arms must be recognized, therefore, as hyperbolic humanitarian catastrophizing, or as we say in business, “marketing hype.”

In conclusion, while hyping of the size, scope, and impact of the illicit aspects of the arms trade was a de facto condition for first building consensus and momentum for the PoA, the ATT, and programs like CASA ISACS, continuing to do so presents serious reputational risk. [20] Continuing to assert that proliferation of small arms in society is intrinsically a bad thing for humanity presents serious reputational risk as well. Ultimately, such apparent dishonestly in the pursuit of otherwise admirable humanitarian goals raises questions about hidden agendas, credibility, integrity, and subject matter expertise. If the UN and humanitarian organizations really want to advocate for the safety of humanity around the globe, honesty is still the best policy.

About The Author

Jeff Moran, a Principal at TSM Worldwide LLC, is a business consultant specializing in the international defense, security, and firearms industries. He studies negotiations & policy-making at the Executive Masters Program of the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva, Switzerland. Previously Mr. Moran was a strategic marketing leader for a multi-billion dollar unit of a public defense & aerospace company, a military diplomat, and a nationally ranked competitive rifle shooter. Jeff Moran has an MBA from Emory University’s Goizueta Business School and a BSFS degree from Georgetown University’s Walsh School of Foreign Service.

End Notes

[1] For more on this Program of Action see the Conference Report http://www.un.org/events/smallarms2006/pdf/192.15%20(E).pdf and http://www.poa-iss.org/PoA/poahtml.aspx. It is important to note that the Conference and the Program of Action were preceded by what is known as the UN Firearms Protocol. The Protocol is formally known as the United Nations General Assembly Resolution A/RES/55/255 and has the full title of “Protocol against the Illicit Manufacturing of and Trafficking in Firearms, Their Parts and Components and Ammunition, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime,” adopted 31 May 2001. This document is available here.

[2] United Nations General Assembly, “Towards an arms trade treaty: establishing common international standards for the import, export and transfer of conventional arms”, Resolution A/RES/61/89, adopted 18 December 2006. This document is available here

[3] United Nations General Assembly, “The Arms Trade Treaty,” Resolution resolution A/RES/64/48, adopted 2 December 2009. This document is available here.

[4] Ibid.

[5] http://www.poa-iss.org/CASA/CASA.aspx

[6] Ibid.

[7] View the welcome page for the UN CASA website as of 9 June 2012 here.

[8] View the partnership page for the UN CASA website as of 9 June 12 here.

[9] Alina Kaczorowska. Public International Law. Fourth Edition. Routledge: 2010. P.26-30. See Article 38 of the Statue of the International Court of Justice here.

[10] Small Arms Survey, established in 1999, is supported by the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, and by sustained contributions from the Governments of Canada, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. The Survey has received funding from the Governments of Australia, Belgium, Denmark, France, New Zealand, Spain, and the United States, as well as from different United Nations agencies, programmes, and institutes.

[11] See mission of Small Arms Survey here.

[12] November 4, 2011. This author was a note-taker and participant in this seminar, which was hosted by the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies.

[13] This is taken from official US government mortality statistics managed by the Centers For Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The date range for this statistic was from 1993, a peak year, to 2009, the most recent year for which age-adjusted data is available as of June 2012. Raw source data is available here. See graph and table at end of document for more information.

[14] http://www.gallup.com/poll/150353/self-reported-gun-ownership-highest-1993.aspx?version=print

[15] See footnote 13 for population numbers in the table, same date range and data source.

[16] Rachel Stohl and Susan Grillot. The International Arms Trade. Polity Press: 2009. P. 93

[17] Owen Greene and Nicholas Marsh, eds. Small Arms, Crime and Conflict: Global Governance and the Threat of Armed Violence. Routledge: 2012. P. 90.

[18] http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs//2010/dc3247.doc.htm and http://www.un.org/disarmament/convarms/SALW/

[19] Owen Greene and Nicholas Marsh, eds. P. 91.

[20] Anna Stavrianakis. Taking Aim At the Arms Trade: NGOs, global civil society, and the other world military order. Zed Publishing Ltd: 2010. P. 143-4.

—

Graph and Table Reference For Endnote 13

First Published: 14 June 2012

Last Updated: 11 February 2015

Republication and redistribution are authorized when author Jeff Moran and URL https://tsmworldwide.com/dishonest-humanitarianism/are cited. See other published items at https://tsmworldwide.com/category/published/.